I told you Jennifer Hecht has good breaking stuff. The curveball she hurls in today’s reading is wicked, especially coming right on the heels of Brandon’s report on our cultural “happy pill” addiction the other afternoon:

I told you Jennifer Hecht has good breaking stuff. The curveball she hurls in today’s reading is wicked, especially coming right on the heels of Brandon’s report on our cultural “happy pill” addiction the other afternoon:

“It is a modern myth that some mood drugs are good and some are bad… our public rhetoric is mythically against drugs, and yet our individual lives include all sorts of intoxicants, stimulants, antidepressants, and other happiness drugs.”

Sounds like maybe she’s going to defend a libertarian loosening of attitudes and statutes on this hot-button issue, maybe even defend the idea that psycho-pharmacology promises a royal road to happiness? But then the pitch veers sharply through the zone and it’s past you. Before the final pitch of this inning (“Drugs”) she “would not counsel the use of illegal drugs for happiness… if you get caught, you won’t be happy.”

Alright, I’ll drop the baseball metaphor. World Series doesn’t start ’til Wednesday. (I’m picking the Yanks in six.) But Hecht’s approach to drugs is not easy to score. I think the best angle on it is from William James’s famous, notorious remarks on alcohol:

“It is part of the deeper mystery and tragedy of life that whiffs and gleams of something that we immediately recognize as excellent should be vouchsafed to so many of us only in the fleeting earlier phases of what in its totality is so degrading a poisoning.”

And:

“The sway of alcohol over mankind is unquestionably due to its power to stimulate the mystical faculties of human nature, usually crushed to earth by the cold facts and dry criticisms of the sober hour. Sobriety diminishes, discriminates, and says no; drunkenness expands, unites, and says yes. It is in fact the great exciter of the Yes function. . . . Not through mere perversity do men run after it. ”

Some might call alcohol and other intoxicants “artificial,” but James is not pointing to the genesis of an episode of imaginative flight but, rather, emphasizing the resultant expansiveness, the sense of cosmic unity and affirmation, and the general feeling of existential reconciliation. These are not �artificial, no matter the instigating agency. They are vehicles of transcendence. But subjectivity and transcendence are not unqualified goods; they are rimmed by relations of consequence that must figure prominently in our final evaluations.

I think that’s Hecht’s approximate position, too. We’re “trapped in our era’s assumptions and anxieties” about chemicals, legal and otherwise, and she wants to snap us out of our trance so we can think more clearly about the admissible limits of self-medication and its possible contributions to our happiness.

James again: “How at the mercy of bodily happenings our spirit is… [A] cup of strong coffee at the proper moment will entirely overturn for the time a man’s view of life. Our moods and resolutions are more determined by the condition of our circulation than by our logical grounds.”

James again: “How at the mercy of bodily happenings our spirit is… [A] cup of strong coffee at the proper moment will entirely overturn for the time a man’s view of life. Our moods and resolutions are more determined by the condition of our circulation than by our logical grounds.”

(Nice pun, Willy. As one who begins every day with strong coffee and thrives under its influence, I take particular interest in this passage. I remain confident that my better early-morning moments are mine and not Starbucks’.)

Hecht: “You were happy today. Does the fact that you had two cups of strong coffee and a dose of over-the-counter painkiller have anything to do with our assessment of this happiness?”

Could be. “Imagine that coffee beans could be cultivated so that they packed more of a euphoric punch.” Yeah!

And what if it wasn’t coffee, but something flatly illegal?

And what if it wasn’t coffee, but something flatly illegal?

How about it, John Prine?

Or Bertie Russell? “I am not prepared to say that drugs can play no good part in life whatsoever.” Moments when a wise physician will prescribe opiates are “more frequent than prohibitionists suppose.”

Hecht: “We have drugs that can help make people happy– short-term bliss, long-term grins.” We should think about it. And we should think about all the money we’re wasting on all the wrong wars.

All that said, I confess that I’m no Tim Leary or Albert Hofmann (his obit) or Aldous Huxley. I don’t even like nitrous oxide. Coffee, beer, and whisky are my drugs of choice. I don’t believe I abuse them, though I’m not going to ask my GP to review my position on that.

I do agree with Huxley, though: “I cannot discover that I was any stupider (under the influence) than I am at ordinary times.” I have occasionally experienced “that state of uninhibited and belligerent euphoria which follows the ingestion of the third cocktail.” And you know what? I liked it.

Hecht: “When we drink alcohol we can think about it as a possibility for minor metaphysical events, not only as a technique to numb ourselves. We can see it as a different kind of intelligence rather than as stupidity.”

But be VERY careful, don’t overestimate your intelligence, and don’t drive. (Dr. Hofmann was very lucky, on his bicycle. And for the record, he made it to 102 but his son, an alcoholic, died at 53.)

And if you’re ingesting something of more ramifying impact, don’t skip class , don’t neglect your children or other relationships or your health and mental stability. “Here are some of the things long-term happiness requires in the short term: studying for exams; caring for children… being responsible at work; forgiving friends and spouses who have hurt you terribly; keeping the promises of marriage… taking a walk…” There’s more, but I have to go walking now.

See you in class.

P.S. Happy birthday, Older Daughter! (Don’t read this post ’til you’re 21.)

terrorizing tales of eternal torment. That’s why there are so many adult hell-raisers still abroad in the 21st century.

terrorizing tales of eternal torment. That’s why there are so many adult hell-raisers still abroad in the 21st century. It’s the autumn of ’86, the Statue of Liberty’s just been

It’s the autumn of ’86, the Statue of Liberty’s just been  “Actively involved with both family and students, redesigning and rebuilding one home and designing and building another from scratch– all while finishing a book almost three thousand pages long in manuscript– William

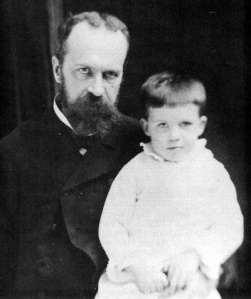

“Actively involved with both family and students, redesigning and rebuilding one home and designing and building another from scratch– all while finishing a book almost three thousand pages long in manuscript– William James was constructing his life with all the energy he had.” A time of career achievement, and a time of warm and cozy domesticity. (That’s his Irving Street study on the left, and Chocorua on the right.) James seems comfortably at home in his universe.

James was constructing his life with all the energy he had.” A time of career achievement, and a time of warm and cozy domesticity. (That’s his Irving Street study on the left, and Chocorua on the right.) James seems comfortably at home in his universe. anything but heroic while he stood silently beyond the circle of his family. The formula of his happiness, Nietzsche insisted, was “a yes, a no, a straight line, a goal.” But a formula is not enough.

anything but heroic while he stood silently beyond the circle of his family. The formula of his happiness, Nietzsche insisted, was “a yes, a no, a straight line, a goal.” But a formula is not enough. I told you Jennifer Hecht has good breaking stuff. The curveball she hurls in today’s reading is wicked, especially coming right on the heels of Brandon’s report on our cultural “happy pill” addiction the other afternoon:

I told you Jennifer Hecht has good breaking stuff. The curveball she hurls in today’s reading is wicked, especially coming right on the heels of Brandon’s report on our cultural “happy pill” addiction the other afternoon: James again: “How at the mercy of bodily happenings our spirit is… [A] cup of strong coffee at the proper moment will entirely overturn for the time a man’s view of life. Our moods and resolutions are more determined by the condition of our circulation than by our logical grounds.”

James again: “How at the mercy of bodily happenings our spirit is… [A] cup of strong coffee at the proper moment will entirely overturn for the time a man’s view of life. Our moods and resolutions are more determined by the condition of our circulation than by our logical grounds.”

And what if it wasn’t coffee, but something flatly illegal?

And what if it wasn’t coffee, but something flatly illegal? Curtain call for the law-giver, exodus-leader, and alleged miracle-worker

Curtain call for the law-giver, exodus-leader, and alleged miracle-worker  “The Good of man is the active exercise of his soul’s faculties in conformity with excellence or virtue…Moreover this activity must occupy a complete lifetime; for one swallow does not make spring, nor does one fine day; and similarly one day or a brief period of happiness does not make a man supremely blessed and happy.”

“The Good of man is the active exercise of his soul’s faculties in conformity with excellence or virtue…Moreover this activity must occupy a complete lifetime; for one swallow does not make spring, nor does one fine day; and similarly one day or a brief period of happiness does not make a man supremely blessed and happy.” Speaking of miracles…

Speaking of miracles… But for myself, Emerson’s words in the

But for myself, Emerson’s words in the  knew that this daily miracle shines, as the character ascends. But the word Miracle, as pronounced by Christian churches, gives a false impression; it is Monster. It is not one with the blowing clover and the falling rain.”

knew that this daily miracle shines, as the character ascends. But the word Miracle, as pronounced by Christian churches, gives a false impression; it is Monster. It is not one with the blowing clover and the falling rain.” It’s 1883, James is 41 and a success in his chosen vocation (about to be promoted to full professor). Like many who marry relatively late, it’s taken him awhile to settle comfortably into the group dynamic of family life and the checks it inevitably places on a bachelor’s accustomed unconditioned freedom. But settle he has, and the stability and safe haven of home are reflected in the growing confidence of his philosophic voice.

It’s 1883, James is 41 and a success in his chosen vocation (about to be promoted to full professor). Like many who marry relatively late, it’s taken him awhile to settle comfortably into the group dynamic of family life and the checks it inevitably places on a bachelor’s accustomed unconditioned freedom. But settle he has, and the stability and safe haven of home are reflected in the growing confidence of his philosophic voice. “

“ and he refuses to accept the notion that whatever is real is always conceptually and nominally precise. Language is limited. It dulls our powers of discernment and discrimination. Non-verbal experience is rich, but difficult to contain and identify. It acquaints us, for instance, with vague feelings of relation (like the feeling of “if,” “and,” or “but”) that are no less real than more substantive things. It is evanescent, impressionistic, fluid, streamy.

and he refuses to accept the notion that whatever is real is always conceptually and nominally precise. Language is limited. It dulls our powers of discernment and discrimination. Non-verbal experience is rich, but difficult to contain and identify. It acquaints us, for instance, with vague feelings of relation (like the feeling of “if,” “and,” or “but”) that are no less real than more substantive things. It is evanescent, impressionistic, fluid, streamy.

a serial philanderer and early “free love” enthusiast– said parenting had been his greatest joy. “The secret to happiness is this: let your interests be as wide as possible, and let your reactions to the things and persons that interest you be as far as possible friendly rather than hostile.’

a serial philanderer and early “free love” enthusiast– said parenting had been his greatest joy. “The secret to happiness is this: let your interests be as wide as possible, and let your reactions to the things and persons that interest you be as far as possible friendly rather than hostile.’ Finally, Hecht has standards. Reminding us of Pyrrho’s famous pig, who impressed

Finally, Hecht has standards. Reminding us of Pyrrho’s famous pig, who impressed