We’re talking today about the ideas of Professor Scott Pratt (U. of Oregon), who visited our campus last spring and planted the seed of my interest in our course topic. Don’t know much about native and indigenous wisdom but I’m having fun learning.

NOTE TO STUDENTS: Class canceled today. Check your email.

From Scott’s website:

In my book, Native Pragmatism: Rethinking the Roots of American Philosophy, I argued that the philosophical views of Native Americans played a significant role in the origins of classical pragmatism-the philosophies of John Dewey, CharlesPeirce, and William James. By examining both the Native American philosophical traditions that emerged in the interaction between indigenous Americans and Europeans, and the ways in which the work of seminal European American philosophers developed, I argued that a case can be made for the influence of Native American thought. In particular, I looked at the work of Roger Williams, Benjamin Franklin, and Lydia Maria Child, the Native American traditions that they encountered, and ways in which these interactions contributed to a developing and distinctive American philosophy. Among the aspects of native thought that were most influential, I argued, was the principle of pluralism…

When Scott visited us last Spring he began with a series of creation myths from the Tualatin people of the Pacific Northwest. In each rendition, successive native epochs are eventually transmuted into non-human natural forms. Each gains from its respective creation story a coherence and inner relatedness that binds the people to one another, to the land and climate, to time and place. Each tale somehow “liberates” its tellers from the threat of stolen or wrongfully-assimilated identity. In the aggregate, the tales stand together as a pluralistic unity: just the relatedness to please a good pragmatist.

Such stories may strike the literalizing western-scientific ear as quaint, charming, but irrelevant. Native thinkers and their sympathizers instead applaud their instructive attention to Mother Earth, and their receptivity to her lessons.

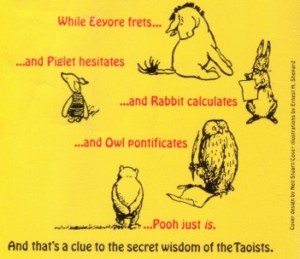

Pratt’s pragmatic-compatibilist thesis is that we can learn from such native American traditions, without compromising our commitment to the scientific story. The native point of view is inherently pluralistic. The scientific image, so far, has not been.

Calling the earth and its people a “creation” may hang up those of us who’ve grown weary of the stale Intelligent Design squabbles of recent years, but the indigenous focus is not on the idea of a divine Singularity event that produced the cosmos. It is not even meant to contradict the evolutionary emphasis on natural processes of development over time. It is meant to underscore the inclusive relatedness and sacred spirituality of everything. With the right spin, it’s nothing Darwin wouldn’t welcome. Or a Darwinian like E.O. Wilson.

But it might be un-Christian. Everything means everything, in the claim that everything and everyone is sacred and already “saved” by its natural provenance. If you’re really a sacred part of the whole, you can’t fall. You don’t need to be redeemed. You don’t need a missionary to rescue you from paganism.

George Tinker had a beautiful dream of pluralism. How practical is it? Well, how practical was MLK’s? More than it seemed in 1962, for sure. Same goes for the Lakota phrase mitakuye oyasin, and its inclusive/pluralistic disposition towards creation.

Daniel Wildcat’s vision– which we’ll begin to explore in greater detail next class– is not merely meditative, but “co-active” and pragmatic.

Here’s our puzzle and challenge: how to honor the wisdom of native tales like that of the Skyhomish, who imagined a primordial tribal council setting the path of the river, and the “school” version that invokes only physics and geography? Are these really complementary “knowledges,” the mutual preservation of which makes us smarter? The solution, if there is one, will look forward to fruits. It won’t try to lock down the one true story and exclude all others. Is that too plural? Or just plural enough?

==

FYI, for those wishing to understand and possibly emulate the spiritual journey of Ed Chigliac: The First Unitarian Universalist Church of Nashville is offering a course called “The Shamanic Journey,” February 2–March 2:

FYI, for those wishing to understand and possibly emulate the spiritual journey of Ed Chigliac: The First Unitarian Universalist Church of Nashville is offering a course called “The Shamanic Journey,” February 2–March 2:

Interested in learning an ancient form of healing and self-knowledge? Sian Wiltshire, our intern minister, who has been a shamanic practitioner for almost a decade, will be offering a class on the shamanic journey—the central spiritual practice of shamans around the world. Bring your curiosity and your questions to this five-part class. Please bring with you a pillow, blanket, any rattle or drum you may have (not required), and a journal or paper to write on. Norbert Capek Classroom (Morgan House), 1808 Woodmont Blvd., Nashville