I’m excited for the start Monday afternoon of our summer “focused study” of The Anglo-American Mind, wherein we’ll tack and attempt to navigate various “cross-currents in British and American thought, exploring ways in which classic thinkers on both sides of the pond have mutually influenced and reacted to each other.”

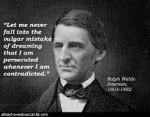

And, continues the official and possibly over-ambitious course description, “we’ll also read and discuss the likes of William Wordsworth, Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Sanders Peirce, Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, David Hume, Anthony Trollope….” Well, maybe. Never hurts to build your metaphorical castles in the air.

The English wit Oscar Wilde once said “we have really everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language.” I wish I’d said that, Oscar, but I will. It’s an exaggeration, of course, but in service of the defensible premise we set out from: Americans and Brits do have a special relationship, culturally and philosophically, and a motivated study of its various lines of mutual relatedness promises amusement, clarity, and light. It’ll be fun.

Our main texts: Pragmatism by William James, On Liberty by J.S. Mill, English Hours by Henry James, and Jay Hosler’s whimsical, graphical look at Charles Darwin’s peripatetic style of reflection, The Sandwalk Adventures.

We begin with the first four lectures of Pragmatism, starting with this question:

- Why do you think James dedicated Pragmatism to the memory of J.S. Mill (“from whom I first learned the pragmatic openness of mind and whom my fancy likes to picture as our leader were he alive today”)?

There’s no short and simple answer to that, but one intriguing thread connects them: both suffered bouts of emotional despondency, and both turned to the poetry of William Wordsworth to pull them out of it.

The Mill-Wordsworth connection is familiar, having been prominently featured in the fifth chapter of his Autobiography.

For though my dejection, honestly looked at, could not be called other than egotistical, produced by the ruin, as I thought, of my fabric of happiness, yet the destiny of mankind in general was ever in my thoughts, and could not be separated from my own. I felt that the flaw in my life, must be a flaw in life itself…

This state of my thoughts and feelings made the fact of my reading Wordsworth for the first time (in the autumn of 1828), an important event of my life. I took up the collection of his poems from curiosity, with no expectation of mental relief from it, though I had before resorted to poetry with that hope… But while Byron was exactly what did not suit my condition, Wordsworth was exactly what did…

What made Wordsworth’s poems a medicine for my state of mind, was that they expressed, not mere outward beauty, but states of feeling, and of thought coloured by feeling, under the excitement of beauty. They seemed to be the very culture of the feelings, which I was in quest of. In them I seemed to draw from a source of inward joy, of sympathetic and imaginative pleasure, which could be shared in by all human beings; which had no connection with struggle or imperfection, but would be made richer by every improvement in the physical or social condition of mankind. From them I seemed to learn what would be the perennial sources of happiness, when all the greater evils of life shall have been removed. And I felt myself at once better and happier as I came under their influence… I needed to be made to feel that there was real, permanent happiness in tranquil contemplation. Wordsworth taught me this, not only without turning away from, but with a greatly increased interest in, the common feelings and common destiny of human beings. And the delight which these poems gave me, proved that with culture of this sort, there was nothing to dread from the most confirmed habit of analysis… The result was that I gradually, but completely, emerged from my habitual depression, and was never again subject to it. J.S. Mill, Autobiography

Less familiarly known is the James-Wordsworth connection, newly spotlighted in William James Studies (Spring 2017, vol.13, no.1) by David Leary in “Authentic Tidings”: What Wordsworth Gave to William James” (PDF):

As regards James’s later psychological and philosophical work, the critical insights that distinguished his way of thinking revolved around the Wordsworthian convictions that the human mind is active; that it has its own interests; and that its feelings are as significant – perhaps even more significant – than its thoughts…

James gave expression to “the mind’s excursive power,” as Wordsworth put it.38 (Wordsworth’s use of this phrase underscored that his poetically described excursion through countryside and mountains was an allegory for the mind’s ability to wander, in imagination, around objects, assuming different perspectives, seeing reality now from this and now from that point of view.

“The mind’s excursive power” – that’s what we’ll be tracking, and tracking with, in our course. There’s even been talk of field trips into the rolling middle Tennessee countryside, as we wander in search of Anglo-American minds (which really ought to be pluralized in the course title as well).

Also noteworthy, in the vein, is the appreciative WJ Studies note by biographer Robert Richardson (Emerson, Thoreau, James), on John Kaag’s wonderful American Philosophy: A Love Story:

Kaag leaves us with what Goethe, Emerson, and William James all agreed on. In the beginning was not the word, but the deed, the act. The way forward is not twelve steps, or ten or three. It’s just one. Don’t sleep on it, sit on it, stand on it, or take it for a trial spin. Take the step, You have to do what you can, and you have to do it right now.

Well alright then, let’s get moving!

(This post marks my experimental return to Up@dawn (version 1) as a primary publishing venue. Up@dawn 2.0 is for now set up to receive and store these posts, via IFTTT. But it doesn’t much matter when or where we mark dawn’s revelations, morning is still (as Henry said) whenever I am awake and there is a dawn in me.)

via Blogger http://ift.tt/2rx2qtu