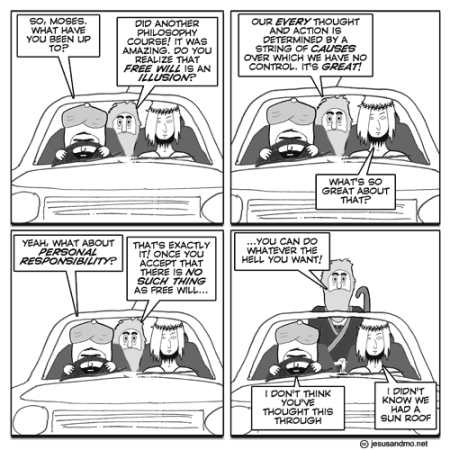

So, about that particular “Jesus and Mo” cartoon I mentioned here and in class yesterday, the one I like to use to introduce the free will/divine foreknowledge problem, the one a couple of students thought contrary to the spirit of cosmopolitan “citizen of the cosmos” acceptance of difference we’d been discussing in connection with Anthony Appiah’s PB interview…

Maryam Namazie has some thoughts on standing by our Author.

Some atheists are not happy with One Law for All’s use of the Jesus and Mo cartoon on leaflets to promote the 11 February Day in defence of free expression [in the UK]. They feel that since the Jesus and Mo cartoons have been deemed offensive, it is best not to use them.

But that’s the whole point isn’t it? We’re rallying in order to say that the right to offend is part of free expression. No one needs to rally for inoffensive speech, do they?

Free expression is a big part of the point, and offense is something one can choose not to take.

But the issue for me is not about whatever “insult” might attend the scenario of cartoon caricatures depicted in bed, reading and talking. Author’s simply reminding us that the Abrahamic faiths have a great deal more in common than their fervent partisans want to admit.

No, the issue is really to do with whether we’re up for an open exploration of ideas, diversity, and “the value of different points of view.”

The man who has not read is like the man who has not traveled — he is not an intelligent critic, for he has nothing with which to compare what falls within the little circle of his experiences… That to which we are accustomed we accept uncritically and unreflectively. It is difficult for us to see it somewhat as one might see it to whom it came as a new experience. George Fullerton

When we read a text or gaze at an image that makes us uncomfortable or angry or hurt, we’re broadening the circle of our experience. We’re “traveling” to the land of someone else’s consciousness, someone else’s way of seeing. If I can invoke one more metaphor, we’re putting on and viewing the world through someone else’s glasses.

And that’s what I try to do in my philosophy classes: get everybody talking, swapping glasses, seeing things as others see them.

You don’t believe in god? Slip on the Augustine or Anselm or Descartes- Rx lenses: clearer or fuzzier? Think you’re essentially an immaterial spirit? Take a gander through these Hobbes specs: matter in motion, finely resolved.

You believe in god? Here, Julia Sweeney, try the no-god glasses for a second.

…Let’s just try on the not-believing-in-God glasses for a moment, just for a second. Just put on the no-God glasses and take a quick look around and then immediately throw them off. So I put them on and I looked around.

I’m embarrassed to report that I initially felt dizzy. I actually had the thought, “Well, how does the Earth stay up in the sky? You mean, we’re just hurtling through space? That’s so vulnerable!” I wanted to run out and catch the earth as it fell out of space into my hands.

And then I thought, “Oh yeah, gravity and angular momentum is gonna keep us revolving around the sun for probably a really long time.” Then I thought, “What’s going to stop me from just, rushing out and murdering people?” And I had to walk myself through it, why are we ethical? Well, because we have to be. We’re social animals. We’re extremely complex social animals. We evolved a moral sense, like an aversion to wanton murder, in order for communities to exist. Because communities help us survive better in much bigger numbers. And eventually we codified these internal evolved ethics inside of us into laws against things like wanton murder. So… I guess that’s why I won’t be rushing out and murdering people! …[Begins at 1:32]

The aim is not uniform vision or a permanent “correction,” necessarily, just a momentary glimpse of insight that may eventually improve our mutual understanding and lessen the tension and mistrust between us. It may make us slightly less blind to one another’s various ways of seeing and being in the world.

Guess who said this?

And now what is the result of all these considerations and quotations? It is negative in one sense, but positive in another. It absolutely forbids us to be forward in pronouncing on the meaninglessness of forms of existence other than our own; and it commands us to tolerate, respect, and indulge those whom we see harmlessly interested and happy in their own ways, however unintelligible these may be to us.

Hands off: neither the whole of truth nor the whole of good is revealed to any single observer, although each observer gains a partial superiority of insight from the peculiar position in which he stands. “On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings“

No, not Monty Python.

Now… ready to try the google glasses?