“Life is so short, questionable and evanescent that it is not worth the trouble of any major effort… no man is ever very far from [suicide]… Life has no genuine intrinsic worth… Human life must be a kind of error, [as is] the notion that we exist in order to be happy.”

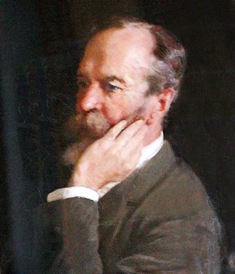

“Life is so short, questionable and evanescent that it is not worth the trouble of any major effort… no man is ever very far from [suicide]… Life has no genuine intrinsic worth… Human life must be a kind of error, [as is] the notion that we exist in order to be happy.” Thus spake Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), a man of many antipathies and little affection for the world.

Young Schopenhauer became a hero to the youthful “romantics” of his time who were so committed to feeling (as opposed to reason), championing “the whole person” against pure and abstract reason, emphasizing the importance of the irrational and thus foreshadowing Kierkegaard (1813-1855), “the melancholy Dane”. Nietzsche (1844-1900), not a contemporary or party pal, was briefly smitten with him. He was one of Wittgenstein‘s (1889-1951) favorite philosophers.

Young Schopenhauer became a hero to the youthful “romantics” of his time who were so committed to feeling (as opposed to reason), championing “the whole person” against pure and abstract reason, emphasizing the importance of the irrational and thus foreshadowing Kierkegaard (1813-1855), “the melancholy Dane”. Nietzsche (1844-1900), not a contemporary or party pal, was briefly smitten with him. He was one of Wittgenstein‘s (1889-1951) favorite philosophers.

He fell in love but “had no wish to formalize the arrangement”– a classic case of reluctance to commit. Alain de Botton calls him “Dr. Love,” but “his refusal to marry his mistress and mother of his child at a time when this would deeply damage her social and economic status is hardly the behavior of a loving spirit.” It’s not a stretch, though, to imagine his metaphysics being very different if his early interpersonal encounters had gone differently.

Schopenhauer admired his countryman Goethe for turning so many of the pains of love into knowledge. But Goethe‘s weltanschauung was very different: “If you wish to draw pleasure out of life you must attach value to the world.”

Schopenhauer did attach some value to some parts of the world, such as his succession of dogs. He also (reports de Botton) loved Venetian salami, theatre, the opera, the concert hall, novels, philosophy, poetry, and at least one or two women.

So: why didn’t he have a more positive experience of life? Or did he, after all, enjoy living– and complaining about it? Would he have had a better life if he had learned to be more optimistic, more grateful, and less critical? Or is he one of those people whose temperament thrives, somehow, under conditions of self-imposed adversity?

Schopenhauer on love. “The conscious mind is a partially sighted servant of a dominant, child-obsessed will-to-life… we would not reliably assent to reproduce unless we first had lost our minds.” And we would not be sexually or romantically attracted to another person if we weren’t under the domination of that inexorable, insatiable Will… “Love is nothing but the conscious manifestation of the will-to-life’s discovery of an ideal co-parent…”

In other words, nature’s willful agenda is all about biology and procreativity. Nothing more. What’s love got to do with it? Not much, it’s all just so much romantic window-dressing concealing the inexorable, impersonal, driving will of the universe and its progeny to self-replicate, ad nauseum. As Arthur saw it, this is a function that finds us on all fours with all the beasts of creation. Our sentimental soft-core re-framing of sex in the language of love and affection does nothing to blunt its hard-core reality: “An animal is born. It struggles to survive. It mates, reproduces, and dies. Its offspring do the same, and the cycle repeats itself generation after generation. What could be the point of all this?” (Passion for Wisdom) Simply, says A.S., the continuation of the race. Period.

The spectacle of it all may be entertaining, for those who like to watch as well as participate. But it’s not ennobling or elevating or ultimately happy-making, just because we write songs and poems and Hallmark cards and dirty books about it. It’s merely, as Isabella Rossellini says, Green Porno. But what makes mechanistic sex between snails and whales and worms (et al) titillating here is the presence of Isabella in a cheesy snail/whale/worm costume. The human presence, specifically the participation in such acts of a consciousness we can relate to, raises the stakes and changes the game. Schopenhauer seems not to have appreciated that, reducing love, romance, and affection to impersonal fecundity. Sad. Stupid.

“The pursuit of personal happiness and the production of healthy children are two radically contrasting projects. We pursue love affairs, chat in cafes with prospective partners and have children with as much choice in the matter as moles and ants – and are rarely any happier.”

So: those of us who think our marriages and the subsequent births of our children were transcendently-joyous events are just deluded.

The World as Will and Idea (1819) contended that the sole essential reality in the universe is the will, and all visible and tangible phenomena are merely subjective representations of that ‘will which is the only thing-in-itself’ that actually exists. ( Squashed Ph’ers)

Like the Buddhists, he recommended asceticism and the blunting of desire. Like Nietzsche, he thought art and aesthetic

experience were redemptive. “The essence of art is that its one case applies to thousands…no longer one man suffering alone, he is part of the vast body of human beings who have throughout time fallen in love in the agonizing drive to propagate the species” and just maybe, in the process, find love and meaning and purpose.

He may have been a grinch, a sourpuss, a misanthrope, and a misogynist, but as W.C. Fields said: no one who loves children or animals is all bad. Schopenhauer loved dogs and loathed the restriction of their freedom by man.

He may have been a grinch, a sourpuss, a misanthrope, and a misogynist, but as W.C. Fields said: no one who loves children or animals is all bad. Schopenhauer loved dogs and loathed the restriction of their freedom by man.

“You would think that a philosopher who named his pet poodle “Atman” would have the ability to see the Self in all beings; yet Arthur Schopenhauer’s love of wisdom did not seem to extend to a general love of humanity. In fact whenever the poodle misbehaved Schopenhauer would refer to it as “You Human”. -R.Udovicich, The Poodle Named Atman

“The pursuit of personal happiness and the production of healthy children are two radially contrasting projects.” This from a life-long, childless bachelor. He literally did not know whereof he spoke.

“An inborn error: the notion that we exist in order to be happy… the erroneous notion that the world has a great deal to offer.” And yet… Schopenhauer finally transcends pessimism, at least on paper. By assigning the absurdities of existence to an implacable, impersonal force of will, he comes to look less at his own individual lot than at that of humanity as a whole. He conducts himself more as a knower than as a sufferer.

But of course we can’t really know that the world is nothing but will. That’s Schopenhauer’s peculiar interpretation and perspective. In an odd way, though, it reconciled him to a life he claimed to find intolerable – and seems even to have made it worth living, from that perspective.

If I could sit down with old Arthur I’d like to share a poem with him. Sometimes, by David Budbill, begins:

Sometimes when day after day we have cloudless blue skies,

warm temperatures, colorful trees and brilliant sun, when

it seems like all this will go on forever…

And continues:

when I am so happy I am afraid I might explode or disappear

or somehow be taken away from all this,

at those times when I feel so happy, so good, so alive, so in love

with the world, with my own sensuous, beautiful life, suddenly

I think about all the suffering and pain in the world, the agony

and dying. I think about all those people being tortured, right now,

in my name.

And concludes:

But I still feel happy and good, alive and in love with

the world and with my lucky, guilty, sensuous, beautiful life because,

I know in the next minute or tomorrow all this may be

taken from me, and therefore I’ve got to say, right now,

what I feel and know and see, I’ve got to say, right now,

how beautiful and sweet this world can be.

Arthur would probably hate it. He’d love hating it, and he’d love writing big dense fat books about how much he hated it.

“Sweet,” indeed.

Ricard quotes “the great pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer,” and his coupling of striving and desire. The

Ricard quotes “the great pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer,” and his coupling of striving and desire. The  implication is that desire always frustrates, is “everywhere impeded,” always struggling, fighting, suffering. We can escape desire, or suppress it. But Mark

implication is that desire always frustrates, is “everywhere impeded,” always struggling, fighting, suffering. We can escape desire, or suppress it. But Mark  “Take any demand however slight, which any creature, however weak, may make. Ought it not, for its own sake, to be satisfied? If not, prove why not. The only possible kind of proof you could adduce would be the exhibition of another creature who should make a demand that ran the other way. The only possible reason there can be why any phenomenon ought to exist is that such a phenomenon actually is desired. Any desire is imperative to the extent of its amount; it makes itself valid by the fact that it exists at all.”

“Take any demand however slight, which any creature, however weak, may make. Ought it not, for its own sake, to be satisfied? If not, prove why not. The only possible kind of proof you could adduce would be the exhibition of another creature who should make a demand that ran the other way. The only possible reason there can be why any phenomenon ought to exist is that such a phenomenon actually is desired. Any desire is imperative to the extent of its amount; it makes itself valid by the fact that it exists at all.”  keep our cool, resist pointless anger, and practice a little tough love (as well as loving-kindness) with the rule-breakers. Don’t be

keep our cool, resist pointless anger, and practice a little tough love (as well as loving-kindness) with the rule-breakers. Don’t be  Young

Young

He may have been a grinch, a sourpuss, a misanthrope, and a misogynist, but as W.C. Fields said: no one who loves children or animals is all bad. Schopenhauer loved dogs and loathed the restriction of their freedom by man.

He may have been a grinch, a sourpuss, a misanthrope, and a misogynist, but as W.C. Fields said: no one who loves children or animals is all bad. Schopenhauer loved dogs and loathed the restriction of their freedom by man.